This post is a lightly edited transcript of my presentation at ResearchED Bournemouth on Saturday 7 June. In it, I explore how we can grow leadership capacity in schools, not through roles or titles, but through the everyday conversations and habits that shape culture of a school. The talk draws on coaching principles, research evidence, and practical experience to offer a more human, sustainable vision of school leadership.

This post is a lightly edited transcript of my presentation at ResearchED Bournemouth on Saturday 7 June. In it, I explore how we can grow leadership capacity in schools, not through roles or titles, but through the everyday conversations and habits that shape culture of a school. The talk draws on coaching principles, research evidence, and practical experience to offer a more human, sustainable vision of school leadership.

I have worked in and with a number of schools now, and there’s a pattern I’ve seen more than once. It starts when leadership stops listening.

At first, it’s subtle: line management becomes checklist-driven, staff voice is limited to a yearly staff survey with opaque outcomes, and decisions start arriving fully formed. Over time, people stop speaking up, not because they don’t care, but because they don’t feel it will make a difference. They have lost agency at this stage.

You see, leadership isn’t only about making decisions. It’s about creating the conditions where others can — where people feel seen, heard, and able to apply agency from wherever they stand. That is what I mean by developing leadership capacity.

That experience, and the questions it raised, led me to the work I’m sharing with you today. This, then, is about how we build leadership from within, and how we use everyday interactions to grow something more meaningful, more sustainable, and more human.

(My) Understanding (of) Leadership Capacity

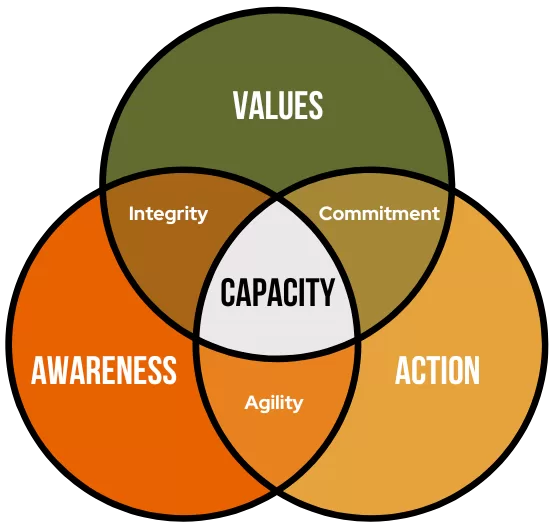

We often talk about leadership capacity as though it’s something reserved for those next in line for promotion. But in reality, leadership capacity isn’t about hierarchy or job titles; it’s about influence, clarity, and the ability to respond to complexity with integrity.

Capacity exists wherever people make decisions, form relationships, and affect others — whether or not they hold formal leadership titles. It’s about how people respond under pressure, how they communicate purpose, and how they model the values of the organisation.

And here’s the crucial point: capacity is cultivated through reflective practice and relational trust (awareness), and through consistent alignment between what we say we value and how we act.

- Integrity: values + awareness → clarity of stance.

- Agility: awareness + action → wise adaptation.

- Commitment: values + action → follow-through.

Capacity is what’s possible when all three are present — when leadership stops being done to you and starts being done with you.

Why It Matters

Too many leadership programmes don’t always prepare people to think reflectively or to navigate ambiguity. The Peter Principle tells us that people are often promoted based on success in their old role, not their capacity for the new role. Hence the brilliant teacher turned overwhelmed Head of Department.

At the same time, schools suffer from initiative fatigue. In my experience, SLT don’t set out to be toxic — they’re simply unprepared. Overwhelmed leaders become reactive leaders. And reactive leaders cling to shiny new solutions promising transformation.

Leadership pipelines often feel like musical chairs: you’re next, whether you’re ready or not. And when we mistake confidence for readiness, we miss the deeper developmental work.

Haili Hughes’ work on instructional coaching, echoing Jim Knight, emphasises respectful, dialogic coaching grounded in equality rather than hierarchy. Hughes warns against coaching becoming a buzzword. Done well, it is one of our most effective forms of professional learning.

The NFER’s McLean & Worth remind us that teachers rarely leave because of one factor. They leave because autonomy, belonging, and professional growth are eroded over time.

These are the core drivers of Self-Determination Theory. Coaching can create the conditions for these needs to be met.

Agency — not autonomy for its own sake — is key. As Dylan Wiliam says: “Love the ones you’re with.” Invest in the teachers you have — not to fix them, but to help everyone get better.

Using the Compass to Develop Capacity

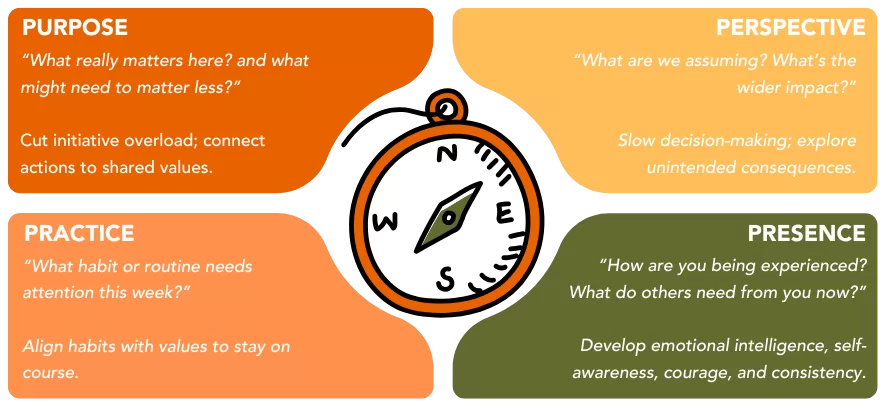

The Leadership Compass provides four bearings — Purpose, Perspective, Presence, Practice — that guide leadership conversations.

- Purpose: eliciting someone’s “why”; aligning values with mission.

- Perspective: widening their field of view; sense-making beyond the task.

- Presence: emotional intelligence; asking “What does your team need from you right now?”

- Practice: consistent habits; embedding reflection; using observation protocols.

You don’t need to be a coach to use this — just intentional in your crucial conversations.

An Example from Practice: Line Management as Insight, Not Oversight

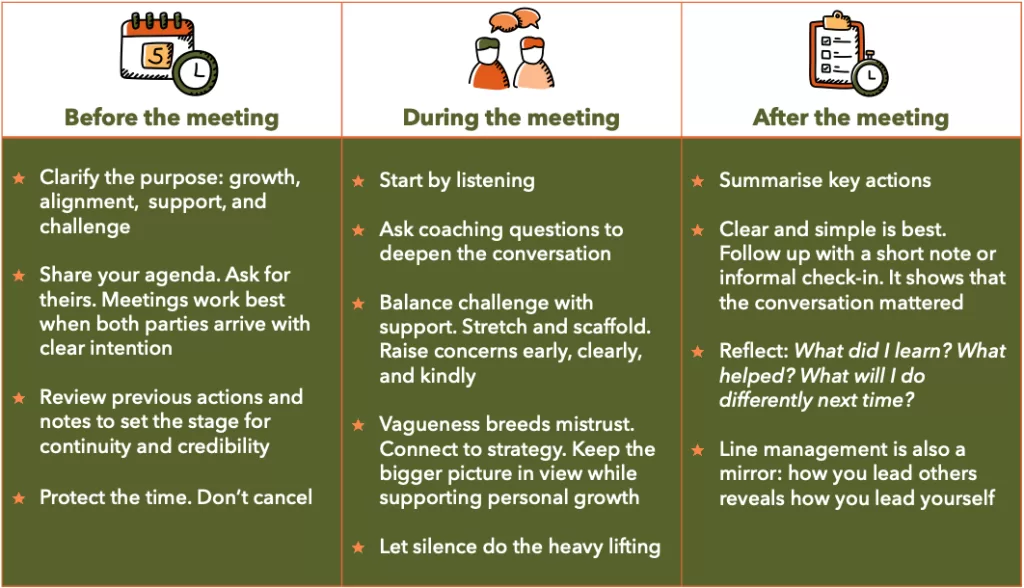

Before the meeting: be clear on purpose; share agendas; never cancel — it signals priority.

During the meeting: listen first; ask coaching-informed questions; raise concerns kindly; keep strategy visible; let silence do the heavy lifting.

After the meeting: follow up; reflect on your own practice.

I see line management less as oversight and more as insight.

Closing Thought: The Compass Is Not a Map

The schools that thrive are not the ones with flashy initiatives, but those with leaders who are consistent, deliberate, and reflective.

The Compass won’t give you certainty. A compass doesn’t show you where you’re going — but it shows you how to get there.

You can view and download the slides below:

Ledership-Compass-ReaseachEd-070625

References and Further Reading

Buck, A. (2016). Leadership Matters. John Catt.

Deci & Ryan (2000). The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits. Psychological Inquiry.

Education Endowment Foundation (2021). Effective Professional Development.

Hughes, H. (2021). Mentoring and Coaching in Education. Crown House.

Knight, J. (2007). Instructional Coaching. Corwin Press.

McLean & Worth (2021). Teacher Autonomy and Retention. NFER.

Wiliam, D. (2016). Leadership for Teacher Learning.

Brown, B. (2018). Dare to Lead. Random House.

“Leadership is not about being in charge. It is about taking care of those in your charge.”

— Simon Sinek

Photo by cottonbro studio

One Comment