This post is a lightly edited transcript of my presentation at ResearchED Bournemouth on Saturday 7 June. In it, I explore how we can grow leadership capacity in schools, not through roles or titles, but through the everyday conversations and habits that shape culture of a school. The talk draws on coaching principles, research evidence, and practical experience to offer a more human, sustainable vision of school leadership.

I’ve worked in and with a number of schools now, and there’s a pattern I’ve seen more than once. It starts when leadership stops listening.

At first, it’s subtle: line management becomes checklist-driven, staff voice is limited to a yearly staff survey with opaque outcomes, and decisions start arriving fully formed. Over time, people stop speaking up, not because they don’t care, but because they don’t feel it will make a difference. They have lost agency at this stage.

You see, leadership isn’t only about making decisions. It’s about creating the conditions where others can, where people feel seen, heard, and able to apply agency from wherever they stand. That is what I mean by developing leadership capacity.

That experience, and the questions it raised, led me to the work I’m sharing with you today. This, then, is about how we build leadership from within, and how we use everyday interactions to grow something more meaningful, more sustainable, and more human.

(My) Understanding (of) Leadership Capacity

We often talk about leadership capacity as though it’s something reserved for those next in line for promotion. But in reality, leadership capacity isn’t about hierarchy or job titles; it’s about influence, clarity, and the ability to respond to complexity with integrity.

Capacity exists wherever people make decisions, form relationships, and affect others, whether or not they hold formal leadership titles. It’s about how people respond under pressure, how they communicate purpose, and how they model the values of the organisation.

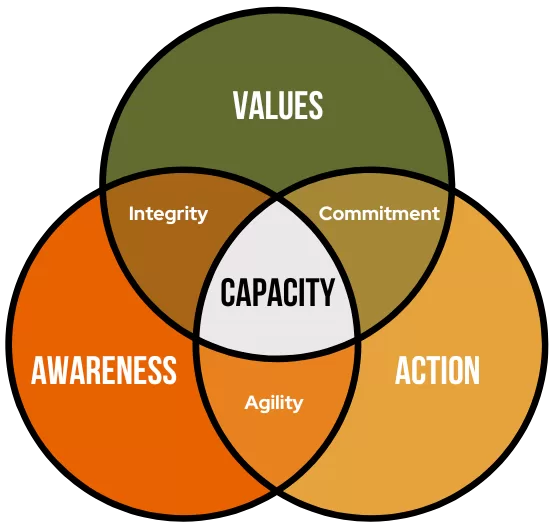

And here’s the crucial point: capacity is cultivated through reflective practice and relational trust (awareness), and through consistent alignment between what we say we value and how we act.

- Integrity emerges when values meet awareness: you know what you stand for and how you are perceived.

- Agility arises from awareness and action: you can read a situation and adapt wisely.

- Commitment sits between values and action: you follow through on what matters, even when it’s hard.

Capacity is what’s possible when all three are present. This is, I think, when leadership stops being done to you and starts being done with you.

Why It Matters

Too many leadership programmes don’t always prepare people to think reflectively or to navigate ambiguity. You may have heard of the Peter Principle, which states that in a hierarchy, people tend to be promoted based on their performance in their current role, irrespective of their capacity for the new role. Teachers too tend to be promoted to positions of leadership because they are great teachers, but later find out they are mediocre Heads of Department.

At the same time, and for altogether not unrelated reasons, schools suffer from initiative fatigue. In my experience, SLT don’t set out to be evil, petty, or toxic. They are just unprepared for the responsibilities their jobs bestow on them, and as a result they become overwhelmed. It is at this point that decision-making becomes reactive, and even erratic. This is when the shiny new initiative, offered by heroes in capes who offers a transformative solution in a shiny package, becomes attractive. And if that doesnt work, they’ll be another one next year.

Leadership pipelines and succession planning often feel like a game of musical chairs. You’re next, whether you are ready or not—sometimes in more than one role! And when we mistake keenness or confidence for readiness, we miss the deeper developmental work that actually builds agency and capacity.

You may be familiar with the work of Professor Haili Hughes on instructional coaching. She strikes a powerful balance between scholarship and practical wisdom. Her approach echoes the work of Jim Knight, the American educationalist and proponent of instructional coaching. Hughes frames coaching as a respectful, dialogic act that is grounded in equality and mutual learning, rather than hierarchy and compliance.

Crucially, Hughes cautions against the dilution of “coaching” into a buzzword, or a sticker for anything vaguely reflective. But properly structured instructional coaching, she reminds us, remains one of the most effective forms of professional development we have. Research from the Education Endowment Foundation supports this, highlighting that well-structured coaching is particularly effective in supporting the application of new strategies in the classroom(I have written previously about this).

Hughes also reframes the so-called “recruitment crisis” as a retention crisis. Drawing on research by Dawson McLean and Jack Worth at the NFER (National Foundation for Educational Research), she noted that teachers rarely leave their schools (or in the gravest cases, teaching altogether) due to a single factor. Instead, teachers are gradually worn down by workload, behaviour, and the erosion of autonomy, belonging, and professional growth.

And indeed, autonomy, belonging, and professional growth are the three drivers from Self-Determination Theory, which identifies them as fundamental psychological needs for intrinsic motivation. Coaching, when done well, can create the conditions for these needs to be met, not through compliance, but through professional conversations.

Agency—not autonomy for its own sake—is key. Agency to me speaks of voice, influence, and participation in shaping one’s own practice. As Dylan Wiliam puts it, we need to “love the ones you’re with.” That means investing in the teachers we already have, not to “fix” them, but to help everyone get better. Not because they’re bad, but because everyone can improve.

What makes instructional coaching powerful is not just what it addresses, but how: through the co-construction of understanding, the surfacing of mental models, and learning from what works.

I think of it as strengths-based coaching (as in the IRIS Connect LEARN model), with the aim shifting from magnifying deficit to amplifying capacity.

In short: teachers should be done with, not done to.

Using the Compass to Develop Capacity

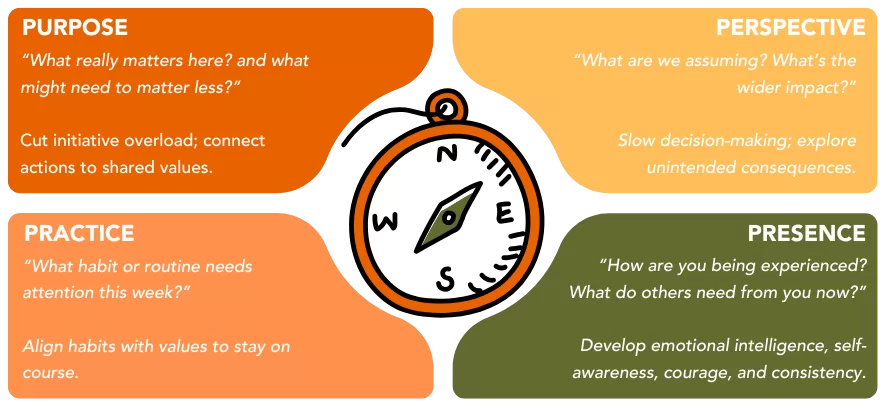

This is where the Leadership Compass becomes, I hope, a useful heuristic. It gives us four bearings(Purpose, Perspective, Presence, and Practice)that can guide crucial conversations and decisions, regardless of whether it is with the people you line manage or with the people who line manage you.

- Purpose: How do we help others connect to their ‘why’?

Using coaching-style questions to elicit purpose.

Inviting colleagues to articulate their contribution to the wider mission, thus aligning values to mission. - Perspective: What wider ripples might this issue create across the school?

Using case studies and working groups to help shift from task tracking to strategic sense-making.

Encouraging secondments, job-shadowing, or cross-departmental or cross-phase conversations. - Presence:What do you think your team needs from you right now?

Developing self-awareness and emotional intelligence. Opening up and modelling feedback as vulnerable dialogue, not as a data-dump or compliance tracking. Ask, Would it have been better if I…? - Practice (or, as I like to call it: consistent action): How do we embed leadership habits?

Making 1:1s and leadership routines developmental, not transactional.

Using observation and reflection protocols to build metacognition, for example by asking: So, when you did (name really effective thing), what was going through your mind?

You don’t need to be a professional coach to use this. You just need to show up to your crucial conversations, especially in line management, with these four bearings in mind.

They give you a way to anchor, explore, and extend your conversations. And over time, they build habits of thought and culture that grow capacity, not just performance.

An Example from Practice: Line Management as Insight, not Oversight

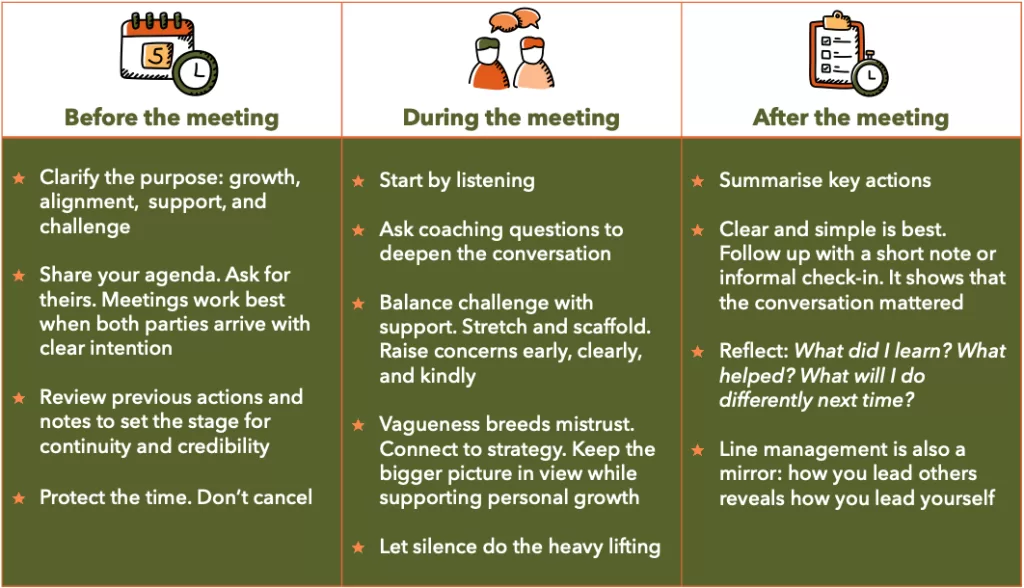

Let’s walk through one of the most routine and powerful opportunities we have to grow leadership capacity: the line management meeting.

Before the meeting, be clear on purpose. Is the meeting about growth? Alignment? Challenge? Let both parties arrive with clarity. Don’t ambush. Share agendas, revisit previous notes. And above all: don’t cancel. You’re signalling what matters.

During the meeting, start by listening, not rushing through a checklist, but asking thoughtful, coaching-informed questions. Stretch and support. Raise concerns clearly and kindly. Brené Brown, the American academic says: Clear is kind, unclear is unkind. Keep the bigger picture visible, linking individual development to wider strategy. And, as Andy Buck often says, let silence do the heavy lifting. Don’t assume you’re here to rescue or fix. You’re here to create space for reflection and to find direction within the person you are with.

After the meeting, follow up. A short note, a question later in the week. And reflect on your own participation: What did that meeting reveal about yourself? What could you do differently next time?

I like to view line management meetings more as insight than as oversight. It’s one of the most powerful opportunities we have to effect positive change.

Closing Thought: The Compass Is Not a Map

The schools that thrive long-term are not the ones with the flashiest initiatives. They’re the ones with leaders, at every level, who lead consistently, deliberately, and reflectively. No heroes, no capes. Just commitment and alignment.

I’ll leave you with this: the Compass won’t give you certainty. A compass is not a map. It doesn’t show you where you are going, but it will show you how to get there.

You can view and download the slides below: a visual summary of the key ideas, frameworks, and prompts shared in the presentation.

Ledership-Compass-ReaseachEd-070625References and Further Reading

Buck, A. (2016). Leadership Matters: How Leaders at All Levels Can Create Great Schools. John Catt.

Deci, E.L., & Ryan, R.M. (2000). The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268.

Education Endowment Foundation (2021). Effective Professional Development. https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk

Hughes, H. (2021). Mentoring and Coaching in Education: A Guide to Coaching Teachers and Leaders. Crown House.

Knight, J. (2007). Instructional Coaching: A Partnership Approach to Improving Instruction. Corwin Press.

McLean, D., & Worth, J. (2021). Teacher Autonomy and Retention. National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER).

Wiliam, D. (2016). Leadership for Teacher Learning: Creating a Culture Where All Teachers Improve So That All Students Succeed. Learning Sciences International.

Brown, B. (2018). Dare to Lead: Brave Work. Tough Conversations. Whole Hearts. Random House.

“Leadership is not about being in charge. It is about taking care of those in your charge.“

— Simon Sinek

Subscribe to my newsletter

- Actionable insights on leadership, learning, and organisational improvement

- Thought-provoking reflections drawn from real-world experience in schools and beyond

- Curated resources on effective practice and digital strategy

- Early access to new articles, events, and consultancy updates

- Invitations to subscriber-only webinars, Q&As, and informal conversations

- Clarity, not clutter—you will not be bombarded by emails

Cancel or pause anytime.

Leave a Reply