In communication theory, latency refers to the time between stimulus and response. Some people respond quickly: we might call them low-latency communicators. They think aloud, process in real time, and speak early and often. Others are high-latency communicators: they pause, observe, weigh implications. Their contributions arrive more slowly, sometimes after others have moved on!

The confident speaker who responds instantly in meetings is frequently perceived as decisive, even strategic. But fluency is not evidence of depth. In fact, quickness can mask superficiality just as slowness can conceal wisdom.

Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow is helpful here. He distinguishes between System 1 thinking (fast, instinctive, automatic)and System 2 thinking (slow, deliberate, effortful). Both have a role. But while System 1 makes us appear decisive, it is System 2 that protects us from the illusion of certainty. And in schools, where complexity is the norm (think curriculum, culture, workload, safeguarding, inclusion…) certainty is often a trap.

That’s why latency matters. The slow-moving challenges schools face are rarely solved by a quick remark or a confident answer. They require what we might call high-latency leadership: a willingness to delay judgement, to dwell in ambiguity, to model the intellectual humility that says, “I’m still thinking.”

The problem is that high-latency leadership is frequently misunderstood. The person who waits, who asks clarifying questions, who says, “Let me reflect on that,” can be seen as hesitant or unconfident. Meanwhile, those who speak with fluency and self-assurance are often assumed to be good strategic thinkers, when in fact it’s just the showmanship that impresses.

This does not have to be a false dichotomy. Schools do need both the leader who can make the urgent safeguarding decision at 8:13am, and the one who sees the long-range implications of a curriculum review or staffing restructure. However, the issue arises when we conflate one for the other, and when we assume that those who can think on their feet are necessarily thinking with their head.

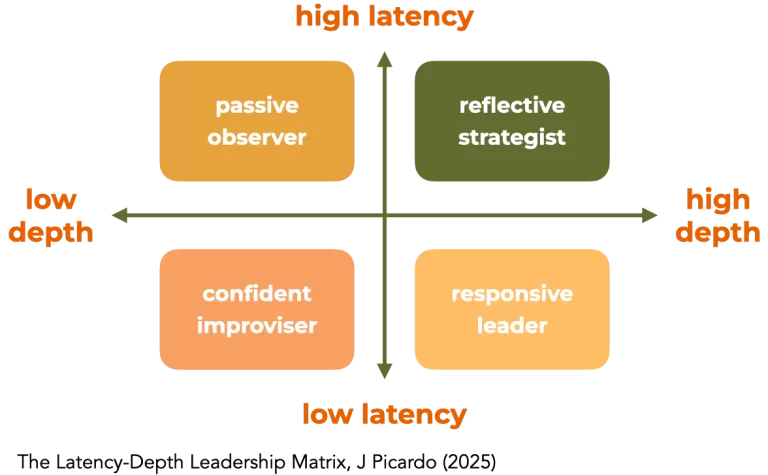

To help navigate this dynamic, I’ve found it useful to visualise leadership behaviour along two dimensions:

- the latency of response (from fast to slow), and

- the depth of thinking (from shallow to strategic).

When these are mapped together, we see four broad leadership archetypes:

The Reflective Strategist (High Latency, High Depth)

Takes time to respond, but when they do, their insight is grounded in long-range thinking, careful listening, and a strong sense of coherence. Not quick to speak, but when they do, it matters.

- Strength: depth, consideration

- Weakness: being underestimated in environments that reward immediacy

The Responsive Leader (Low Latency, High Depth)

Thinks well and acts quickly. Composed in the moment, able to navigate complexity under pressure without losing sight of the bigger picture.

- Strength: decisiveness underpinned by substance

- Weakness: overextension, prone to skipping consultation in pursuit of momentum

The Confident Improviser (Low Latency, Low Depth)

Fluent and persuasive, often with the “gift of the gab.” At ease in meetings, briefings, and public speaking, but prone to surface-level solutions that lack coherence.

- Strength: presence, charisma

- Weakness: dominates meetings, distracts from strategy, and creates confusion downstream

The Passive Observer (High Latency, Low Depth)

Delays or defers decisions, but not for the sake of depth. Struggles to convert thought into clarity or action.

- Strength: caution, resistance to fads

- Weakness: inertia disguised as prudence

Each of these types appears in school senior and middle leadership teams. And most of us move between them, depending on circumstance and confidence. But the danger lies in how we assess others as well as ourselves. The tempation is to reward fluency without questioning the depth of its foundations. Culturally, we tend to applaud those who speak early, loudly, and well, while overlooking the quiet contributor still thinking two layers beneath and five steps ahead.

I’ve seen more than one school fall under the spell of a low-latency leader with a car-salesmansy charm, rehearsed quips, aphorisms, smooth with parents, and fluent in every meeting. But beneath the surface, there’s often no schema. No theory of change. No infrastructure for improvement. Just motion.

The “gift of the gab,” while entertaining, is no substitute for professional judgement. It may entertain a room with canned lines and pop philosophy, but without reflection, it just leadership cosplay.

This matters. Because in meetings, the most fluent speaker often shapes the narrative. And the most reflective ones, who are considering the second- and third-order consequences are left behind, not because they lack insight, but because insight takes time. Schools can be impatient places.

We would do well, then, to make more room for latency. To pause before applauding the confident speaker. To ask what lies beneath the polished response. To recognise that leadership is not a race to speak up, but a responsibility to respond well, whether in the moment or after it. Sometimes, the most thoughtful thing a leader can say in a meeting is, “I’ll come back to you on that.”

”Better to remain silent and be thought a fool than to speak and remove all doubt.

— Popular proverb

2 Comments