”“Every moral panic tells us less about the thing we fear and more about the society that fears it.”

Each generation meets new technology with a pang of moral anxiety. From writing to the printing press, from television to mobile devices, and now AI, we see the same pattern unfold: fear, outrage, control, and eventual acceptance. Perhaps the real lesson isn’t about the technology at all, but about how we manage our own uncertainty.

The Pattern of Panic

When sociologist Stanley Cohen wrote Folk Devils and Moral Panics in 1972, he was describing Britain’s anxious reaction to the Mods and Rockers, but he could just as easily have been describing our relationship with technology today.

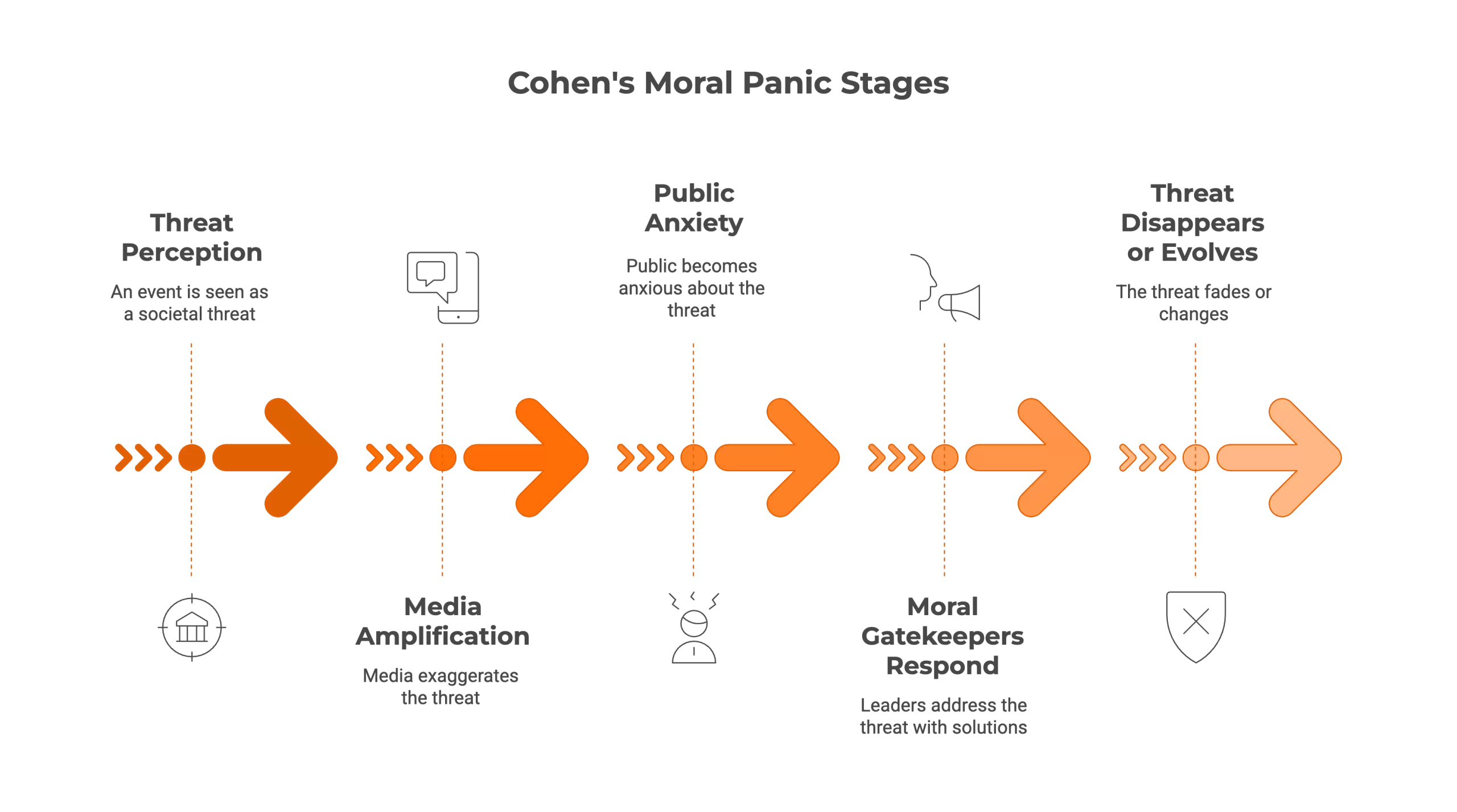

Cohen showed how societies periodically identify a threat to their moral order, amplify it through the media, demand action, and eventually move on, leaving behind new rules, new habits, and lingering guilt.

This five-stage arc (definition, amplification, public concern, institutional response, and decline) has played out many times since: with video nasties, violent video games, social media, and most recently, screen time. Each new technology becomes a mirror for our anxieties about control, childhood, and change.

None of this is to deny that technology brings genuine challenges to attention, privacy, or equity, but rather to note that panic tends to magnify them beyond proportion.

The Screen Time Scare

Few phrases have captured parental unease in my professional experience like “screen time.” In the past decade, it has become shorthand for a moral battleground: too much and you’re negligent; too little and you’re out of touch. The idea that glowing slabs of aluminium and glass are eroding childhood has been repeated so often that it feels axiomatic.

The media helped turn concern into crisis. Headlines about “addiction” and “the lost generation” offered a simple narrative that paints the tech industry as villain, the child as victim, and the parent as powerless. In all this, a myth took hold: that Silicon Valley executives, the architects of our addiction, banned their own children from devices.

Doctors not taking their own medication is a powerful image, but it isn’t quite true. What these tech company executives actually do is parent: they moderate, monitor, and talk with their children. They model and uphold digital boundaries rather than outsource the effort to others. They are not technophobes but digitally literate guides who understand that the goal isn’t prohibition but discernment.

This is not elitism; it’s effective parenting. The myth of total abstinence flatters our panic, but it misses the point. Healthy digital habits come from dialogue, not delegation; from consistency, not coercion; and from parents willing to do the sometimes uncomfortable work of co-regulation, rather than offloading moral responsibility to third parties.

Of course, not every family has equal time or digital confidence. But even small, consistent conversations about how and why we use technology matter more than any parental-control setting.

Déjà Vu: The AI Anxiety

And now, the cycle turns again. Artificial intelligence has become the latest object of moral dread. We are told it will end truth, replace teachers, and hollow out our humanity. In many schools, AI tools are either banned outright or greeted with apocalyptic fascination.

If Cohen were here, he would recognise the pattern instantly:

- Stage one: AI is defined as a threat to learning, creativity, or jobs.

- Stage two: Media amplify extremes, from “superintelligence” to “cheating epidemic.”

- Stage three: Public concern surges, demanding regulation and restraint.

- Stage four: Institutions respond with bans and ethical charters that reassure more than they solve.

- Stage five: The panic will ebb, leaving behind new norms and new moral certainties about what counts as “real” thinking.

Just as with screen time, we risk mistaking anxiety for insight. Of course there are real issues: data bias, academic integrity, safeguarding, surveillance, erosion of trust. But when panic replaces proportion, we end up policing symptoms instead of understanding causes.

From Control to Conversation

What unites these cycles is a sense of loss of control over our children, our work, our sense of what it means to be human and do human things. Yet lasting control is rarely engendered by greater regulation, but rather by better conversation.

Parents who talk to their children about how they use screens and provide structure build discernment and promote self-regulation. Teachers who discuss AI openly with students nurture judgement and discernment. Leaders who explore possibilities and risks together create collective wisdom rather than institutional fear.

Moral panics flare when we mistake novelty for danger. They fade when we remember that the task is not to defend humanity from technology but to express our humanity through it.

Stanley Cohen’s insight remains as relevant as ever: every moral panic is a mirror. What we see reflected there is not the menace of technology, but our struggle to live thoughtfully with the change it habitually brings.

Partnering for Purpose

Through Azimuth, I work with schools and trusts across the UK as a Fractional Digital Strategist, helping leadership teams design and implement digital and AI strategies that are coherent, evidence-informed, and grounded in pedagogy.

This embedded model gives schools access to senior-level expertise without the cost of a full-time post, while ensuring that technology decisions remain purposeful, ethical, and sustainable.

If your school is looking to reconnect its digital strategy with the realities of teaching and learning, I’d love to explore how we could work together.

”I can’t go back to yesterday because I was a different person then.

Alice (from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, by Lewis Carroll)