This piece is written to prompt reflection. School leadership is complex, high-stakes work, often carried out under intense scrutiny and pressure to deliver more with less. The temptation to promise everything to everyone is real, and many of us (myself included) have felt its pull.

My hope is that by naming patterns like cakeism and car salesmanship, we can create space for honest conversations about capacity, priorities, and the trade-offs that shape sustainable progress. This is not a call to do less, nor a criticism from the sidelines, but an invitation to leaders, at every level, to examine our stance, our methods, and the culture we encourage.

The term cakeism, or the belief that we can enjoy all the benefits without accepting any of the costs, came into my consciousness during the Brexit debates, where it became shorthand for a refusal to acknowledge the trade-offs involved in leaving the EU. While the label emerged in a specific political moment, the underlying mindset is not unique to that debate or even to politics; it can be found wherever uncomfortable choices are avoided in favour of comforting, all-gain-no-pain narratives.

On the left, cakeism can appear in the belief that taxing the rich will fund significant improvements without macroeconomic knock-on effects. On the right, it can be found in the claim that tax cuts will pay for themselves through the growth they supposedly trigger. As ever, there are serious, nuanced arguments for and against these policies, but when they are framed as cost-free, the necessary debate over trade-offs is replaced by self-deceiving slogans.

The same dynamic exists in education, though the stakes are local rather than national. Cakeism emerges whenever leaders convince themselves and others that they can achieve better outcomes, with higher quality, without any additional cost or effort. Here, the analogy is not that school leaders are politicians, but that both operate in environments where competing priorities must be reconciled, and uncomfortable realities can be too politically awkward to consider openly.

This is where car salesmanship comes in: a leadership trait I have often observed in schools and other organisations. Its low-latency / low-depth nature thrives in a cakeist culture.

Think of walking into a showroom “just to have a look” and emerging with a car you neither need nor can really afford, persuaded by the charm of the pitch. In schools, the equivalent could be starting with a modest, laudable aim, like, say, improving student wellbeing, and ending up with a whole suite of new initiatives, training programmes, reporting systems, and technology platforms.

In the independent sector, car salesmanship often surfaces when a headteacher seeks to boost admissions with a high-profile transformation. The pitch is irresistible: a world-class academic programme, integrated outdoor education, and specialist enrichment in everything from archery to robotics.

Prospective parents are dazzled at open days, picturing their children fluent in Mandarin and building AI robots by Year 8. What is left unsaid is that the timetable is already overstretched, teachers lack the capacity or expertise to deliver these additions, and the cost of this vision will almost certainly be met by cutting down on less visible but essential provision.

This is classic cakeism: staff already at capacity are expected to lead clubs and even teach new subjects, core academic time is squeezed, and, as a result, the much-hyped wellbeing provision remains more evident in wall displays and brochures than in the lived experience of students.

Car salesmanship can be compelling, but discerning parents on open day tours may notice staff unable to explain details, vaunted trips and initiatives still “in development,” and evasive answers from leaders as to how they will make room for the new initiatives. When academic results eventually dip and teacher turnover rises, students at the trough end of the cycle become the ultimate casualties of this boom-and-bust approach.

However, the leader skilled in car salesmanship also knows how to claim the plaudits during the boom and deflect blame onto others when the bust comes.

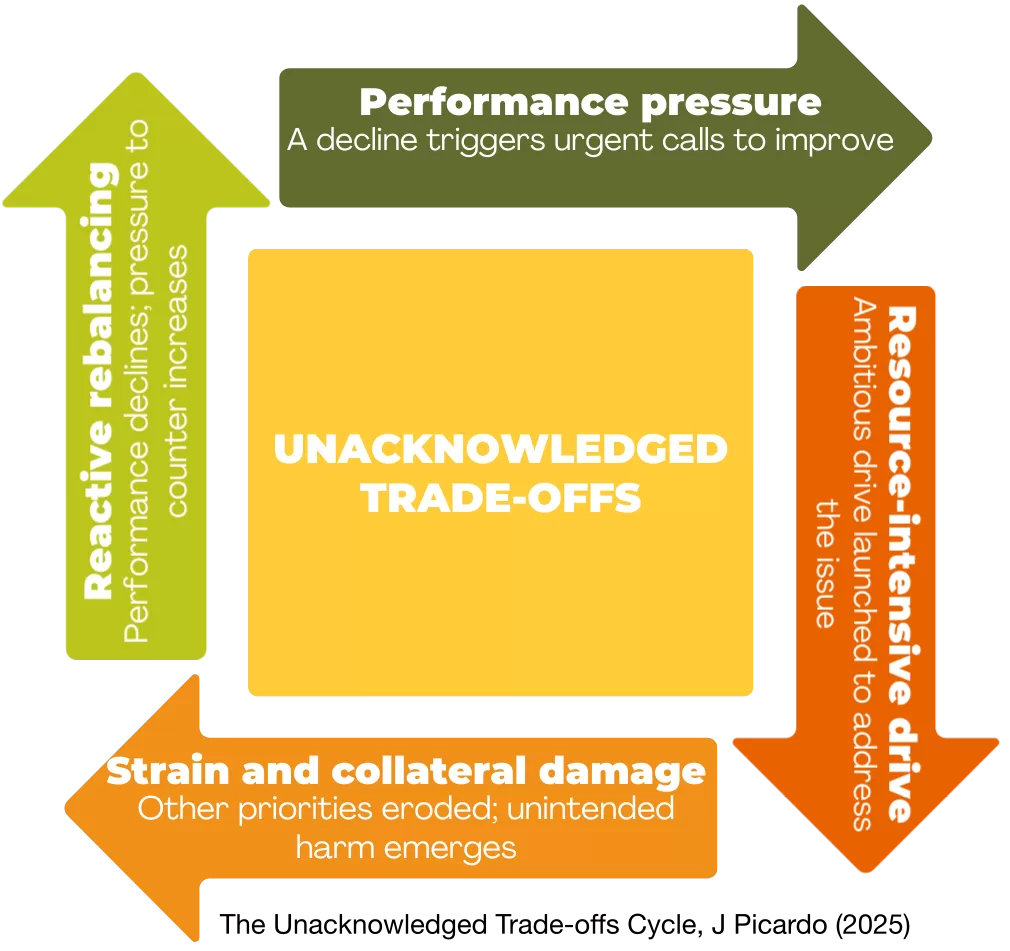

The consequences of this boom-and-bust approach are all too familiar: each surge of activity consumes time and energy, stretching resources to breaking point. The strain erodes other priorities, forcing reactive counter-initiatives that shift focus yet again. In the churn, nothing is embedded well enough to make a lasting difference. Workload intensifies, wellbeing and morale decline, and, over time, trust is steadily worn away.

Staff learn to greet new announcements with scepticism, expecting the burden to fall on them without anything else being scaled back. There is also an ethical cost: the plaudits for bold vision tend to accrue to senior leaders, while the strain of delivery usually falls on those furthest from the decision-making table.

Why does this pattern persist? In politics, attractive promises win votes. In education, inspections, league tables, and parental expectations push leaders to project “boundless optimism” and constant momentum. A cakeist culture rewards the salesperson who can sell the dream, even when the cost is unsustainable.

The antidote is not pessimism but candour. Leaders must have the courage to say, “Yes, we can improve X, but we will need to scale back Y,” and then clearly communicate both the benefits and the trade-offs: good leadership is as much about deciding what to stop doing as it is about what to start.

This means knowing your staff well enough to understand both their capacity and the conditions under which they do their best work. It also means building governance relationships that encourage optimistic realism (yes, of course there is room for optimism!) rather than showmanship, and creating systems for monitoring the impact of initiatives so that resources can be reallocated swiftly when needed. Crucially, it involves resisting the sunk-cost fallacy, which is the tendency to keep pouring time, money, and energy into projects simply because we have already invested in them, and having the courage to stop or scale back when the evidence shows they are not delivering.

This is not about doing less for the sake of it, nor about indulging low expectations; it is about recognising opportunity costs and managing resources intelligently so that energy is directed where it will make the greatest difference.

Cakeism is the belief that we can have it all. Car salesmanship is the method that convinces us to give it a go. Both are seductive. Both carry hidden costs.

Leaders who resist them promise less, but they deliver steady, lasting improvement.

If this piece has resonated with you, I would love to hear your thoughts. Do get in touch or leave a comment.

“There are no solutions. There are only trade-offs.”

— Thomas Sowell

Photo by Ron Lach

A thoughtful and rich reflection here, as always! The issues you touch upon are perhaps bigger still than just individual leaders – as a sector I fear that we are continuing to play into the narrative of the ‘arms race’ between schools, rather than being able to take a step back and look at where the collective gains might be found.

Healthy competition that allows students across the sector to be at the front and centre, rather than an elbows out approach focused more on student acquisition and ‘cakeism’ is absolutely possible but requires a greater collaborative will between school leaders and governors.

Thank you, Paul. That’s so well put. I completely agree that shifting from competition to genuine collaboration is key if we’re to keep students, rather than league tables, at the heart of what we do.