Yesterday I had the pleasure of attending a session with Professor Haili Hughes on instructional coaching at the Bryanston Education Summit. Hughes struck an illuminating balance between scholarship and grounded wisdom, reminding us that coaching, when done well, is not just another professional development fad, but a powerful, evidence-informed lever for meaningful change in schools.

At a time when many school leaders are searching for silver bullets and rely on heroes in capes, Hughes offered a subtler and more sustainable approach: the answers are often already in the room, if only we can learn to listen, to notice, and to think together.

“Love the ones you’re with.”

— Dylan Wiliam

Photo by Mikhail Nilov

Her final point resonated: teachers need to be done with, not done to. It’s a simple distinction, but a profound one. Coaching is effective because it fosters agency and intrinsic motivation, and in doing so, returns dignity to the profession.

At a time when many school leaders are searching for silver bullets and rely on heroes in capes, Hughes offered a subtler and more sustainable approach: the answers are often already in the room, if only we can learn to listen, to notice, and to think together.

“Love the ones you’re with.”

— Dylan Wiliam

Photo by Mikhail Nilov

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

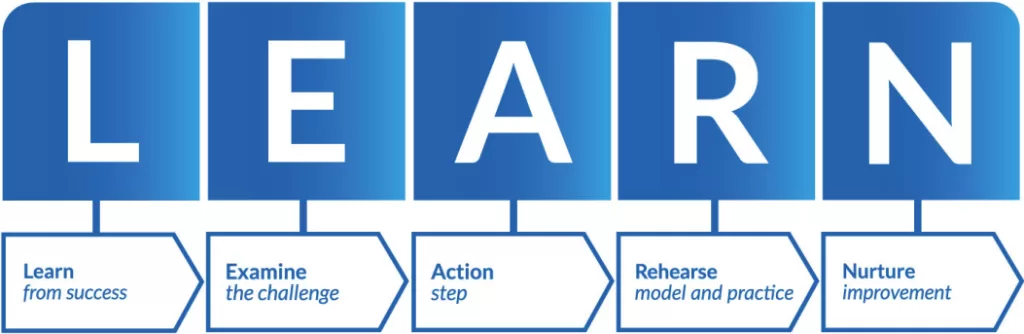

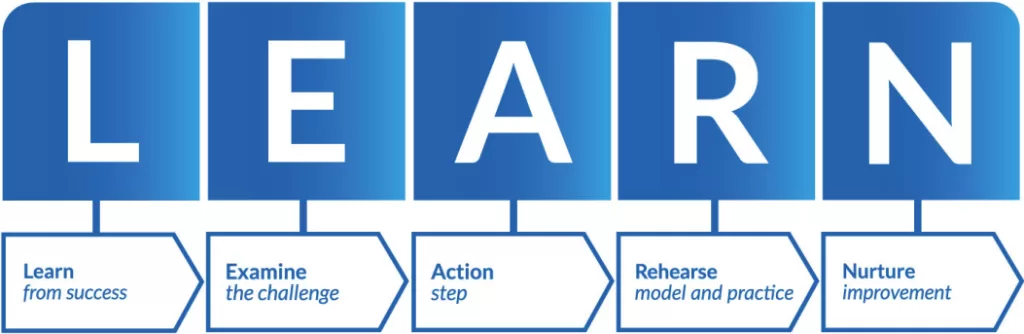

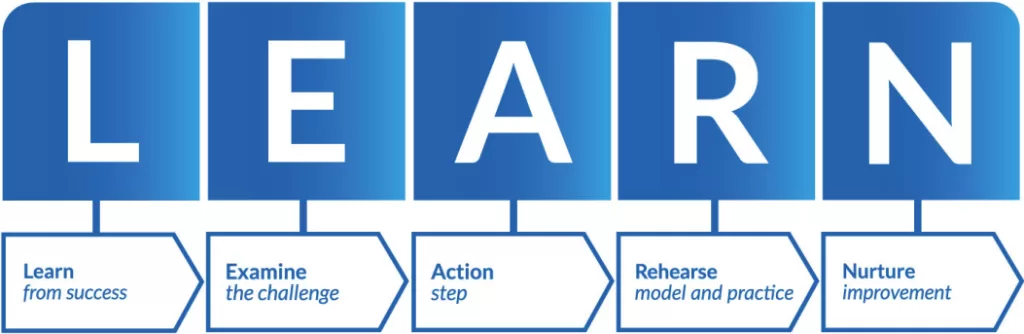

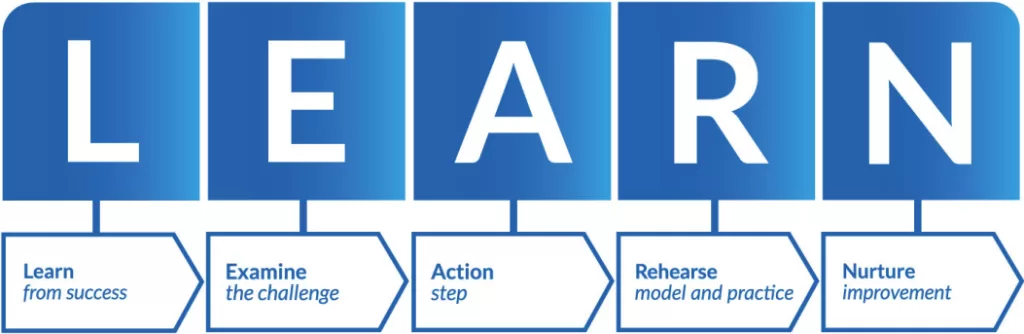

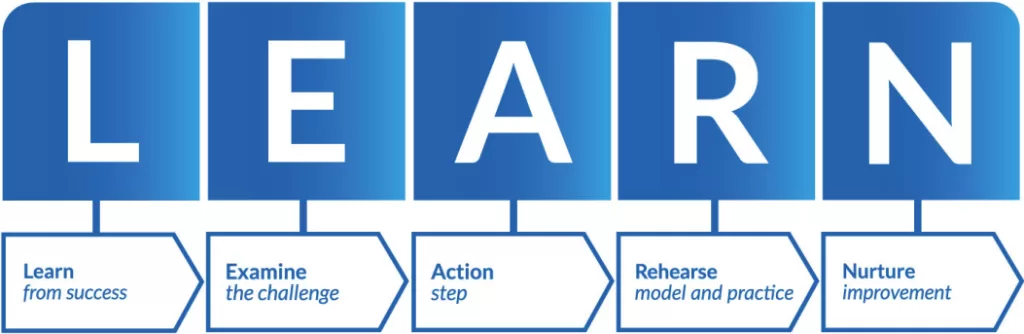

This is where Hughes introduced the IRIS LEARN model and highlighted its focus on “learning from success.” Too often we coach reactively, focusing only on problems or failures. But strengths-based coaching (working from what’s already going well) is not only more motivating, but also more precise. The aim shifts from magnifying deficit to amplifying capacity.

Her final point resonated: teachers need to be done with, not done to. It’s a simple distinction, but a profound one. Coaching is effective because it fosters agency and intrinsic motivation, and in doing so, returns dignity to the profession.

At a time when many school leaders are searching for silver bullets and rely on heroes in capes, Hughes offered a subtler and more sustainable approach: the answers are often already in the room, if only we can learn to listen, to notice, and to think together.

“Love the ones you’re with.”

— Dylan Wiliam

Photo by Mikhail Nilov

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Autonomy, she clarified, should not be misunderstood as unbounded freedom. Schools are necessarily structured organisations. She preferred the term “agency,” which captures voice, influence, and meaningful participation in shaping one’s practice. Coaching creates the conditions for agency, not through compliance, but through conversation.

She cited Dylan Wiliam’s reminder to “love the ones you’re with,” calling for deeper investment in the teachers already in our schools. Instructional coaching, done right, becomes professional development in its truest sense: free of links to formal performance management or capability procedures, and focused not on remediating the supposedly ‘failing’ but on helping all teachers get better. As Wiliam also notes, not because they are bad, but because everyone can improve.

Hughes also tackled the trickier territory of the cognitive complexity in trying to surface and reshape the complex mental models teachers use to navigate the classroom. We cannot see these mental models directly; we can only interpret them through dialogue and conversation. As an example, she suggested that it is more helpful to map the “situational mental model” during lesson observations, which can then be co-constructed into “solution mental models” during coaching conversations.

This is where Hughes introduced the IRIS LEARN model and highlighted its focus on “learning from success.” Too often we coach reactively, focusing only on problems or failures. But strengths-based coaching (working from what’s already going well) is not only more motivating, but also more precise. The aim shifts from magnifying deficit to amplifying capacity.

Her final point resonated: teachers need to be done with, not done to. It’s a simple distinction, but a profound one. Coaching is effective because it fosters agency and intrinsic motivation, and in doing so, returns dignity to the profession.

At a time when many school leaders are searching for silver bullets and rely on heroes in capes, Hughes offered a subtler and more sustainable approach: the answers are often already in the room, if only we can learn to listen, to notice, and to think together.

“Love the ones you’re with.”

— Dylan Wiliam

Photo by Mikhail Nilov

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Importantly, Hughes cautioned against the way “coaching” has become a buzzword or sticker applied onto anything vaguely reflective. But she was keen not to throw the baby out with the bathwater: properly structured instructional coaching remains one of the most effective form of professional development we have. Indeed, research from the Education Endowment Foundation suggests that instructional coaching, when carefully structured and sustained, is a highly effective component of professional development, particularly in supporting the application of new strategies in the classroom.

Hughes also reminded us that what is often called a “recruitment crisis” can be more accurately reframed as a “retention crisis.” Drawing on the work of Dawson McLean and Jack Worth at the NFER, she pointed out that teachers rarely leave because of a single factor. Rather, they are worn down over time by intense and unmanageable workloads, difficult behaviour, and, critically, by a deeper erosion of autonomy, professional growth, and belonging.

These three drivers — autonomy, belonging, and development — align with the well-established Self-Determination Theory by Deci and Ryan, which identifies them as fundamental psychological needs for intrinsic motivation. It is no coincidence, Hughes argued, that these are also the very things that motivated teachers to stay.

Autonomy, she clarified, should not be misunderstood as unbounded freedom. Schools are necessarily structured organisations. She preferred the term “agency,” which captures voice, influence, and meaningful participation in shaping one’s practice. Coaching creates the conditions for agency, not through compliance, but through conversation.

She cited Dylan Wiliam’s reminder to “love the ones you’re with,” calling for deeper investment in the teachers already in our schools. Instructional coaching, done right, becomes professional development in its truest sense: free of links to formal performance management or capability procedures, and focused not on remediating the supposedly ‘failing’ but on helping all teachers get better. As Wiliam also notes, not because they are bad, but because everyone can improve.

Hughes also tackled the trickier territory of the cognitive complexity in trying to surface and reshape the complex mental models teachers use to navigate the classroom. We cannot see these mental models directly; we can only interpret them through dialogue and conversation. As an example, she suggested that it is more helpful to map the “situational mental model” during lesson observations, which can then be co-constructed into “solution mental models” during coaching conversations.

This is where Hughes introduced the IRIS LEARN model and highlighted its focus on “learning from success.” Too often we coach reactively, focusing only on problems or failures. But strengths-based coaching (working from what’s already going well) is not only more motivating, but also more precise. The aim shifts from magnifying deficit to amplifying capacity.

Her final point resonated: teachers need to be done with, not done to. It’s a simple distinction, but a profound one. Coaching is effective because it fosters agency and intrinsic motivation, and in doing so, returns dignity to the profession.

At a time when many school leaders are searching for silver bullets and rely on heroes in capes, Hughes offered a subtler and more sustainable approach: the answers are often already in the room, if only we can learn to listen, to notice, and to think together.

“Love the ones you’re with.”

— Dylan Wiliam

Photo by Mikhail Nilov

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Her session echoed the work of Jim Knight, the American educationalist who frames coaching as a deeply respectful, collaborative act. Knight resists hierarchical metaphors of ‘fixing’ teachers and instead promotes coaching as a dialogue rooted in equality, choice, and mutual learning. In this sense, coaching is not a programme to be implemented but a mindset to be adopted.

Importantly, Hughes cautioned against the way “coaching” has become a buzzword or sticker applied onto anything vaguely reflective. But she was keen not to throw the baby out with the bathwater: properly structured instructional coaching remains one of the most effective form of professional development we have. Indeed, research from the Education Endowment Foundation suggests that instructional coaching, when carefully structured and sustained, is a highly effective component of professional development, particularly in supporting the application of new strategies in the classroom.

Hughes also reminded us that what is often called a “recruitment crisis” can be more accurately reframed as a “retention crisis.” Drawing on the work of Dawson McLean and Jack Worth at the NFER, she pointed out that teachers rarely leave because of a single factor. Rather, they are worn down over time by intense and unmanageable workloads, difficult behaviour, and, critically, by a deeper erosion of autonomy, professional growth, and belonging.

These three drivers — autonomy, belonging, and development — align with the well-established Self-Determination Theory by Deci and Ryan, which identifies them as fundamental psychological needs for intrinsic motivation. It is no coincidence, Hughes argued, that these are also the very things that motivated teachers to stay.

Autonomy, she clarified, should not be misunderstood as unbounded freedom. Schools are necessarily structured organisations. She preferred the term “agency,” which captures voice, influence, and meaningful participation in shaping one’s practice. Coaching creates the conditions for agency, not through compliance, but through conversation.

She cited Dylan Wiliam’s reminder to “love the ones you’re with,” calling for deeper investment in the teachers already in our schools. Instructional coaching, done right, becomes professional development in its truest sense: free of links to formal performance management or capability procedures, and focused not on remediating the supposedly ‘failing’ but on helping all teachers get better. As Wiliam also notes, not because they are bad, but because everyone can improve.

Hughes also tackled the trickier territory of the cognitive complexity in trying to surface and reshape the complex mental models teachers use to navigate the classroom. We cannot see these mental models directly; we can only interpret them through dialogue and conversation. As an example, she suggested that it is more helpful to map the “situational mental model” during lesson observations, which can then be co-constructed into “solution mental models” during coaching conversations.

This is where Hughes introduced the IRIS LEARN model and highlighted its focus on “learning from success.” Too often we coach reactively, focusing only on problems or failures. But strengths-based coaching (working from what’s already going well) is not only more motivating, but also more precise. The aim shifts from magnifying deficit to amplifying capacity.

Her final point resonated: teachers need to be done with, not done to. It’s a simple distinction, but a profound one. Coaching is effective because it fosters agency and intrinsic motivation, and in doing so, returns dignity to the profession.

At a time when many school leaders are searching for silver bullets and rely on heroes in capes, Hughes offered a subtler and more sustainable approach: the answers are often already in the room, if only we can learn to listen, to notice, and to think together.

“Love the ones you’re with.”

— Dylan Wiliam

Photo by Mikhail Nilov

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

2 Comments