The recent Your Undivided Attention podcast, featuring Tristan Harris, Daniel Barcay, Maryanne Wolf, and Rebecca Winthrop, explores the challenges and opportunities that artificial intelligence presents to education.

It is a timely and thoughtful discussion, raising concerns that many educators will recognise. However, the conversation sometimes leans towards familiar patterns of technological alarmism. While many of the concerns are valid, they merit measured reflection rooted in what we already know about teaching, learning and schools.

From Homework to Learning

The suggestion that students can now use AI to instantly complete homework tasks is true, but also not new. Language teachers have long dealt with students pasting their work from Google Translate. The initial fear was soon tempered by experience. Students quickly discovered that getting Google to do the heavy lifting might have got the task done, but not much learning happened in the process. After the peak of the hype, which confidently claimed that language learning was obsolete, teachers adapted, tasks evolved, and the hype over automated translation faded. I suspect we’ll see much the same with generative AI.

However, the claim that there is “no way for teachers to tell” if a piece of work is AI-generated doesn’t entirely hold. While not always easy to prove, there are telltale signs: inconsistent tone, vocabulary that jars with age and stage, unusually literary punctuation, the sudden realisation that they’re, there, and their are actually different words, and an implausible leap into sohisticated analysis of concepts not yet covered. And stacatto sentences. For effect. Most teachers, especially those who know their students well, can usually sense when something is off and do challenge appropriately.

Crisis Talk

The language used in the podcast occasionally slips into crisis mode. Phrases like “the rug has been pulled out from the entire system” or “the old way is fundamentally broken” are striking but ultimately unsubstantiated. Education has met many disruptive moments before—from radio and television to the advent of the internet and now AI—and each time, it evolved rather than collapsed under the weight of its own confidently predicted obsolecence.

Likewise, the idea that we are only now asking the fundamental question, “what is the purpose of education?”, overlooks a rich tradition of educational thought. From Dewey to Piaget to Freire, the aims of education have been debated for decades, especially by those who did not like what they saw. Most would agree that education is about helping young people become thoughtful, knowledgeable, and able to shape their own futures. Some AI applications may support this aim. Others may hinder it. As always, pedagogy should come first.

Technology has always reflected the quality of pedagogy: where teaching is strong, technology tends to enhance it; where it’s weak, technology usually amplifies the flaws.

Attention, Effort and Logical Fallacies

The discussion touches on a widespread belief: that technology (especially social media and smartphones) has undermined attention and critical thinking. While there is some evidence to support this concern, the research remains mixed. It is essential to distinguish between anecdote and evidence, and between the effects of poor design and the potential of well-integrated digital tools. Not all screen time is equal, and not all digital use leads to shallow thinking.

Similarly, the characterisation of classroom technology as a “Faustian bargain” is unhelpfully binary. It assumes that every gain in convenience comes at the cost of something morally or cognitively meaningful. But tools, in themselves, do not carry intent. Outcomes depend on how we use them. Some applications of AI may encourage superficiality, but others may extend access or deepen understanding. The difference lies in design and purpose. Twas always thus with all EdTech.

Something that did chime was the discussion about the value of writing essays as a way to develop thought is rightly emphasised. The process of organising an argument, weighing evidence, and articulating ideas helps build habits of mind that transfer beyond the classroom. If students simply use AI to bypass that process, they won’t develop these skills. But they will know they haven’t. Most learners, in the end, want to understand. When they don’t, they feel it.

Ask any MFL teacher about Google Translate: students do use it to cheat, but usually only until they realise their peers are progressing and they’re standing still.

The Depth of Reading

Wolf’s argument that deep reading is best supported by print is backed by some evidence. Studies suggest that comprehension, particularly of longer and more complex texts, tends to be better on paper. This may be partly due to the distractions built into many digital platforms. However, it’s not the medium alone that matters, but the environment and the way reading is structured. Rather than discarding technology, we should be asking how digital spaces can better support depth.

The idea of “cognitive offloading” is also important. If AI does the hard thinking for students, then learning doesn’t happen. But we should be wary of generalising this principle. Sometimes, offloading routine tasks (like correcting grammar or formatting references) frees up cognitive space for higher-order thinking.

Consider the analogy of buying a car: it’s reasonable to argue that owning one might lead to walking less, and as a result, weaker leg muscles. Taken at face value, that’s probably true. But this conclusion overlooks the fact that exercise can be built into your routine in other way, and that a car can take you to places your legs never could. In short, while cognitive offloading is a valid concern, we shouldn’t assume it will be the dominant or enduring form of AI use.

Technology Mirrors Pedagogy

One contributor comments, approvingly, on not spending “three years memorising multiplication tables”. But the notion that facts no longer matter because they can be looked up remains deeply flawed. We cannot think about what we do not know. Knowledge remains essential. Memory and understanding are not opposed to one another—they are inseparably intertwined.

Perhaps the most useful insight in the discussion is that technology must be integrated intentionally. It will not, by itself, improve learning. Tools mirror pedagogy. When embedded within thoughtful, evidence-informed practice, technology can help. When bolted on without clarity or purpose, it doesn’t.

The cautionary tale of textbook digitisation in countries like Sweden is a case in point. Poor implementation is not the fault of technology itself, but of the decision-making that surrounds it.

The Limits of Personalisation

The podcast discusses different student “modes” of engagement—from passive compliance to active exploration. Much of this rings true and it offers a useful heuristic. Students who are given opportunities to explore and connect learning to real-world contexts often thrive. But it’s misleading to claim that adaptive or personalised learning software necessarily limits this potential. These tools are not inherently narrow. With careful design, technology can support curiosity and inquiry as well as consolidation.

Technology misuse in schools, like students accessing unfiltered content or bypassing learning platforms, is often not evidence of a flawed tool, but of inadequate implementation and oversight. Digital tools must be introduced with clear expectations, training and boundaries. This is a leadership and culture issue as much as a technical one.

Who Designs the Tools?

The point about educators being absent from the design of educational technology is well made. Tools created without teacher input often miss the mark. The depressing example of Google Classroom being developed exclusively by engineers without a background in education highlights the gap between technical capacity and pedagogical insight. Involving educators in the design process isn’t just preferable—it’s essential.

There is though a recognition that AI is having a positive impact in many areas of life, from scheduling bus routes to managing logistics. Education could benefit in similar ways. But at present, much of the technology being developed for schools is shaped by people who are technically skilled but lack a deep understanding of how education works. Too often, EdTech tools are built on simplistic assumptions about teaching and learning.

I do have a degree of sympathy for the many EdTech companies that have leaned heavily on cognitive psychology, developing products that focus narrowly on knowledge acquisition and retention, while crossing their fingers and hoping, perhaps optimistically, that the more complex work of synthesis and understanding will somehow take care of itself. I can only imagine the potential if educators and learning scientists were fully involved from the outset.

Looking Ahead with Clarity

Much of the conversation rightly returns to the idea that we need to prepare children not just for some imagined future, but for the world they already inhabit. AI is here. It is not going away. But how we respond is still up to us. Some uses of AI can ease the load on teachers and support students. Others may erode the core purposes of education if introduced without care.

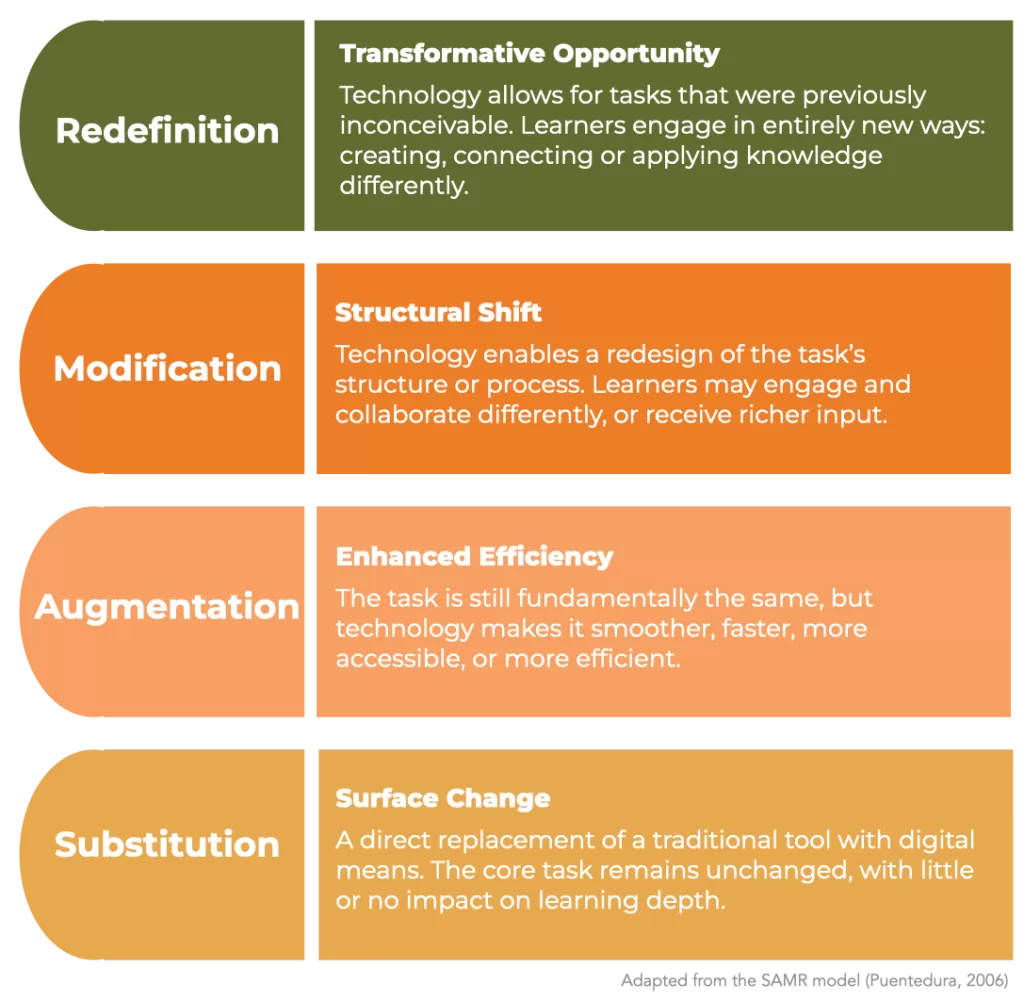

I do balk slightly at the idea that technology is only worthwhile when it redefines tasks. “Does it augment what we’re doing in real life? Does it modify or redefine?” This distinction comes from Puentedura’s well-known SAMR model, which is often misunderstood. It was never meant to establish a hierarchy with redefinition as the ultimate aim, but rather to describe different ways technology can be used. In practice, there is room in schools for all levels of the model. Modifying or augmenting tasks can be just as valuable as redefining them.

The final point is worth underlining though: AI should empower, not replace. The promise of AI tutors in under-resourced contexts is real. But this should not lead to the conclusion that teachers are optional. There is no substitute for human connection, guidance and expertise. Technology can help fill a gap, but it cannot replace the relationship at the heart of good teaching.

Pedagogy First, Always

The podcast raises important questions and points to real challenges. But in responding, we should avoid overstatement and false dichotomies. Education is not in crisis, it is adapting. Technology is not the enemy, it is a tool. My inkling is that AI is not a threat to learning, unless we allow it to replace the work that learning requires.

What matters most is that we keep our heads, avoid jumping to conclusions, and remain anchored in what we know about how people learn. Pedagogy first, always.

If any of this resonates, whether as affirmation, provocation, or polite disagreement, I’d welcome the conversation. These are complex, evolving questions, and we’re better placed to navigate them when we think and talk together. Do comment or get in touch.

“Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral.”

— Melvin Kranzberg

Subscribe to my newsletter

- Actionable insights on leadership, learning, and organisational improvement

- Thought-provoking reflections drawn from real-world experience in schools and beyond

- Curated resources on effective practice and digital strategy

- Early access to new articles, events, and consultancy updates

- Invitations to subscriber-only webinars, Q&As, and informal conversations

- Clarity, not clutter—you will not be bombarded by emails

Cancel or pause anytime.

One Comment